In light of the Trump Administration’s admission of white South African refugees into the United States, the following story that Bensman reported and wrote in December 2001 as a staff writer for The Dallas Morning News covering immigration courts. The 25-year-old story shows this is not the first time the United States provided sanctuary for white Africans ostensibly fleeing forced land redistribution. In the early 2000s, White Zimbabweans fleeing similar land seizures sought safe haven in the United States on claims that their lives were in imminent danger from mobs of black fellow Zimbabwean citizens. Sent or tacitly approved, these “squatter” mobs attacked white families in their remote homes after the Zimbabwean government passed land redistribution laws, supposedly as a corrective to historic colonization that took place centuries earlier. In late 2001, Bensman learned of these unusual black-on-white discrimination asylum cases and reported about one of them for The Dallas Morning News. The current controversy about the Trump administration’s admission of White South African refugees bears remarkable resemblances to what happened with neighboring Zimbabweans back then. Is this what is on the minds of White farmers fleeing South Africa and its new land redistribution law today? Their claims to be fleeing the new land appropriation laws in fear of their lives has drawn ridicule among American liberals as unfounded and their admissions into the United States evidence of white nationalist racism by the Trump administration. But the old story of Zimbabwean whites fleeing their farms on the same kind of claims 25 years ago can perhaps provide some needed context for all further national discussions about this issue.

By Todd Bensman, Staff Writer for The Dallas Morning News, as published December 31, 2001

RICHARDSON, Texas – Dave and Amber Penny heard the news that government squatters in Zimbabwe cut off the nose of a neighbor with a machete when the farmer refused to sign over the deed to his land.

Then another farmer was forced to watch as squatters sexually assaulted his daughters, they said. As the violent government-sponsored invasions of white farms crept closer, the Pennys hoped that the trouble would bypass their 2,300-acre farm. But the campaign, which has killed 77 people and left thousands homeless, reached the family’s farm last year.

Odyssey across continents

The invasion forced the family to embark on an odyssey across three continents that finally ended last month in Dallas. The Pennys were granted political asylum, which came only after they were refused entry four times and their first asylum application was turned down. The family said U.S. officials were reluctant to acknowledge persecution of whites in Zimbabwe before a judge agreed with their claim.

“This has been the most humbling experience of our lives,” Amber Penny said as she and her husband recounted how their family lost the prosperous agribusiness they started from scratch 11 years ago. “We have gone so far down,” she said. “Instead of being the people giving, we’re the people being given to. We are starting from the bottom all over again.”

The Pennys are one of only two white families from Zimbabwe known to have been granted political asylum by the United States. The other family granted asylum declined to comment, citing fear of reprisals against loved ones in the southern African nation. Asylum applications are pending for at least two other families from Zimbabwe living in the Dallas area.

The Dallas attorney who has handled the four cases said immigration officials seem uncomfortable acknowledging persecution of whites in Africa.

“The black Africans are going to say, ‘Give me a break. After years of them suppressing us, look at them claiming we’re suppressing them,'” attorney Michelle Saenz-Rodriguez said. “I think we have a battle there. We’re going to have to educate.”

Gilbert Khadiagala, associate professor of African studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, D.C., said the United States has avoided formalizing a policy of accepting white farmers because of past restrictions on immigration for black Africans. Some may say there is no need for a U.S. policy because Zimbabwe’s white farmers may emigrate to Great Britain without government permission, he said.

“They don’t want to create a separate policy for whites,” he said of the U.S. State Department. “They would be accused of being racist.”

Each year, the United States receives about 35,000 applications for political asylum. The State Department does not release details about who applies for political asylum to protect applicants from reprisal. Immigration records show that about half of the 60 applications filed since January by Zimbabweans – black and white – were denied outright or referred to immigration courts.

State Department officials assigned to Africa issues did not return calls recently to discuss policies for handling the farmers. Earlier this year, Mary Swann, public affairs adviser in the State Department’s Africa bureau, said, “As far as the asylum issue for Zimbabweans, it has not been addressed.”

White farmers urged to stay

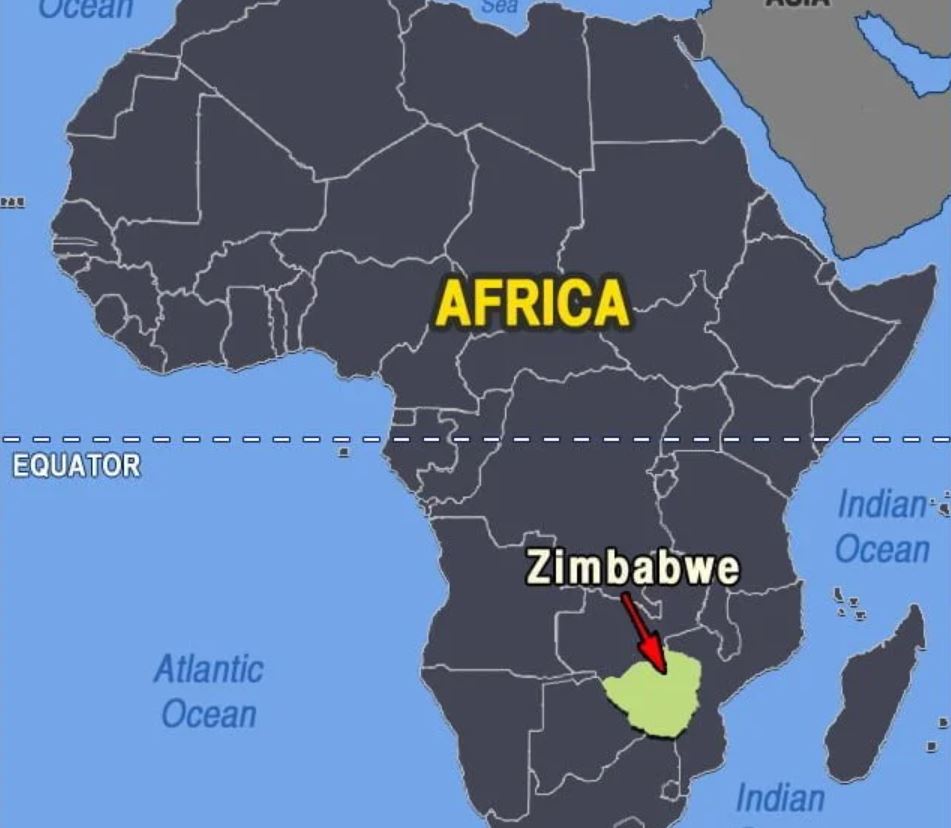

Long before apartheid was dismantled in neighboring South Africa, Zimbabwe was seen as a model of how whites and blacks could live together after blacks replaced white minority rule. Rebels supporting President Robert Mugabe and armed by the Soviet Union achieved independence in 1980 for the country that is about the size of Montana.

White farmers, who make up about 1 percent of the country’s population of 12 million but form the backbone of its economy, were urged to stay as a minority class protected by law. The arrangement has been supported by the United States for 20 years. Facing severe economic problems and an election, Mugabe changed course in early 2000. He has sought to nationalize 4,500 properties – about 95 percent of farmland owned by whites – and distribute the land to supporters.

Since then, government militants backed by local police have been using squatters to force farmers to sign over land and terrorize black laborers. This year, the first white farmers were killed for resisting.

Penny, 40, said he bought the rundown Nassau Farm in 1991 with loans and savings. He said he and his wife slowly built up the place, hiring 140 farmhands and eventually turning healthy profits on corn, flower seed, and cattle. They said their lives with 8-year-old Sarah and 10-year-old Robert were idyllic, centered on the two-traffic-light town of Chinhoyi.

Facing armed squatters

In February 2000, the squatters came.

“We didn’t have any means of protecting our own property because the police were the ones driving all this, and the army,” Penny said. “You just didn’t know who was going to be next.”

Penny said he thinks the squatters invaded his farm because he was training for a marathon with several other farmers, and their runs were presumed to be for covert military purposes. The invasion was sudden and terrifying, he and his wife said.

More than 100 squatters armed with farm implements drove in on 12-ton trucks. Mrs. Penny said she hid with the children inside the wall safe of her home, leaving Mr. Penny to confront the squatters alone.

“They said they were going to cut my white skin off and roast me,” he said. “They said they wanted the farm.”

Mr. Penny said he signed over half the farm under duress. For the next several months, about 16 squatters who camped on the property beat laborers, harassed the children, and halted operations as the Pennys pondered whether to stay or go. They decided to flee to relatives in the United States after discovering that the farm’s foreman had been tortured.

“Every day is just chaos, fighting, intimidation,” Mr. Penny said. “You just want a better life for your family.”

Applying for asylum

U.S. Embassy officials in the Zimbabwe capital of Harare denied them visitor visas, saying they suspected that the family would try to stay in the United States, the couple said. Other farmers were leaving without problems for New Zealand and Britain, where they hold dual citizenship.

“People didn’t go to the U.S. Nobody could get a visa,” Mrs. Penny said. “Our government didn’t want to be seen as the baddies chasing us out of the country.”

Carrying all their possessions in suitcases, the family went to London. Again, the U.S. Embassy denied visitor visas, saying that the family would try to stay. The family moved to Canada, settling into a hotel in Ontario, across from Detroit.

After being denied visas again, the Pennys took a desperate step. A friend drove them – illegally – across the border.

The family came to Dallas, where relatives had put them in touch with Saenz-Rodriguez. She had just helped another Zimbabwean family, believed to be the nation’s first, gain asylum.

After an initial interview in Washington this summer, an immigration official declined to grant the asylum application, saying Penny could not prove he hadn’t persecuted blacks while he was a 19-year-old inductee in the Rhodesian army in 1980.An asylum law provision allows the United States to deny asylum to persecutors.

The case then went to Dallas U.S. Immigration Judge B. Anthony Rogers, who on Nov. 30 awarded the family permanent haven after considering their claim that being white was dangerous in Zimbabwe. The judge declined to comment on the case.

The Pennys now live in a rented Richardson, Texas, duplex. They brought the one item with them from Africa that they treasure most: the deed to their farm. Mrs. Penny has taken a job as a secretary; Mr. Penny is considering his options. Both say they are grateful they can stay in the United States but would go back to their land if the situation improved. They say they feel lucky their children are here.

“Life carries on,” Mr. Penny said.